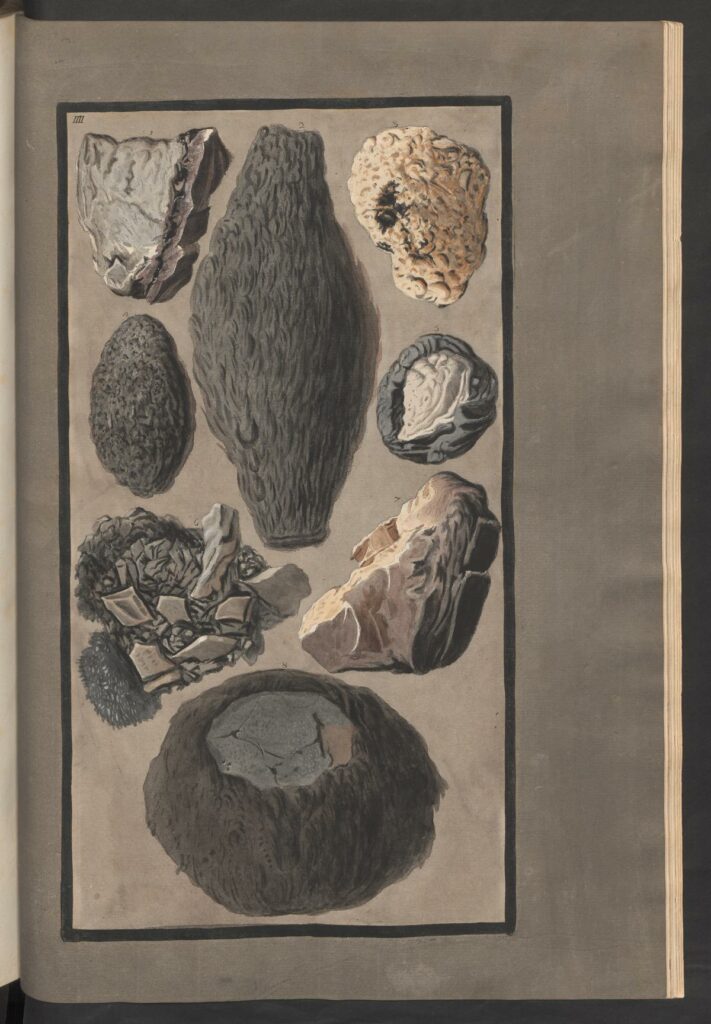

William HAMILTON, Supplement to the Campi Phlegraei, Napoli, Pietro FABRIS (editore nel senso di venditore esclusivo), Francesco MORELLI ? (stampatore) 1779. Tavola IV. Acquaforte colorata a mano, cm. 39 x 21,2 (la tavola). Autore della gouache originale: Pietro FABRIS. Incisore e coloritore: Anonimo.

Nella lettera sulla eruzione del 1779 alla Royal Society, pubblicata nei Supplement e in Philosophical Trasactions, 70, 1780, pp. 42-84, Hamilton annunzia l’invio di campioni di materiali vulcanici da lui raccolti dopo l’eruzione, che, scrive, avrebbero offerto alla vista informazioni migliori della descrizione verbale (Phil. Trans. p. 83: Though I have endeavoured to be as particular and clear as possible in the description I have given of the curious substances produced by the late eruption of Vesuvius, yet, as specimens of those substances will explain more at one sight than I can pretend to do by whole pages in writing, I shall non fall to send you, by the first favourable opportunuty, a collectio of them, which I have set apart for that purpose…). Queste illustrazioni di campioni, assenti nelle Philosophical Transactions, hanno lo stesso scopo. I campioni vesuviani inviati da Hamilton sin dal 1767 passarono dalla Royal Society al British Museum e quindi al Natural History Museum di Londra, dove ora si trovano. Essi non sembrano comunque corrispondere a quelli illustrati nelle tavole dei Campi Phlegraei e del Supplement (Jenkins and Sloan p. 67 e 160 n. 38). In molti esemplari del volume la colorazione a mano ha occultato i numeri delle figure.

Bibliografia. Su Hamilton: Knight 1990, in part. p. 131; Vickers 1997, in part. p. 264; Moore 1994; Thackray 1996; Wood 2006. Sulle vicende editoriali e le tecniche esecutive: Knight 2000, in part. pp. 34-35; Jenkins and Sloan 1996, in part. 165-7. Sul termine bombe vulcaniche tra XVIII-XIX sec.: Nazzaro 2001, pp. 313-4. Sulla eruzione del 1779: Nazzaro 2001, pp. 163-6; Imbò 1984, p. 101; Lirer et al. 2005, p. 59; Ricciardi 2009, pp. 401-11.

ROCCE E DEPOSITI

Bombe vulcaniche

Fatta eccezione per le fig. 1, 3 e 7, verosimilmente tutte le altre figure rappresentano bombe vulcaniche. Questo certamente vale per le fig. 5 e 8 (seconda a destra e ultima in basso) che rappresentano due bombe vulcaniche agglomerate non esplose di forma tonda, con il rivestimento lavico esterno e il nucleo lavico interno, e per la fig. 6 (terza a sinistra) che rappresenta un frammento di bomba esplosa. Hamilton cerca di spiegare la loro formazione e interpreta il nucleo interno come lava antica inclusa in quella eruttata nel 1779:

[p. 25] We found also many fragments of those volcanick bombs that burst in the air […] and some entire, having fall’n to the ground without bursting. The fresh red hot and liquid lava having been thrown up with numberless fragments of ancient lava’s, the latter were often closely inveloped by the former, and probably, when such fragments of lava were porous, and full of bubbles, as is often the case, the extreme outward heat suddendly rarifying the confined air, caused an explosion; when those fragments were of a more compact lava, they did not explode, but were simply inclosed by the lava, and acquired a spherical form by whirling in the air, or rolling down the steep sides of the Volcano.

The shell, or outward coat of the bombs that burst […] was always composed of fresh lava, in which many splinters of the more ancient lava that had been inclosed are seen sticking. I was much pleased with this discovery […].

L’interpretazione delle bombe vulcaniche come pezzi di lava antica rivestiti di lava recente verrà ripresa da Scipione di Breislak, nei Voyages physiques et lythologiques dans la Campanie, Paris, 1801, pp. 258-9, senza menzione di Hamilton: Parmi le pierres lancées dans ces éruptions, on en trouve qu’on a nommées bombes ou balles, suivant leur volume […] Les unes sont des fragmens d’anciennes laves revetue extérieurement de la lave nouvelle...

Per quanto riguarda le fig. 2 e 4 (in alto al centro e seconda a sinistra), Hamilton le interpreta come “drops” di lava recente staccatesi dalla fontana di lava e solidificate (didascalia: N. 2 […] drops from the great fountain of liquid fire […] N. 4 […] These drops are entirely composed of the new lava). Il peso notevole di alcune di esse (p. 27: more than 60 pounds) e il loro aspetto esclude che possa trattarsi della formazione oggi note come “lacrime di Pele” e suggerisce di considerarle come bombe vulcaniche di tipo non agglomerato.

Domenico Laurenza