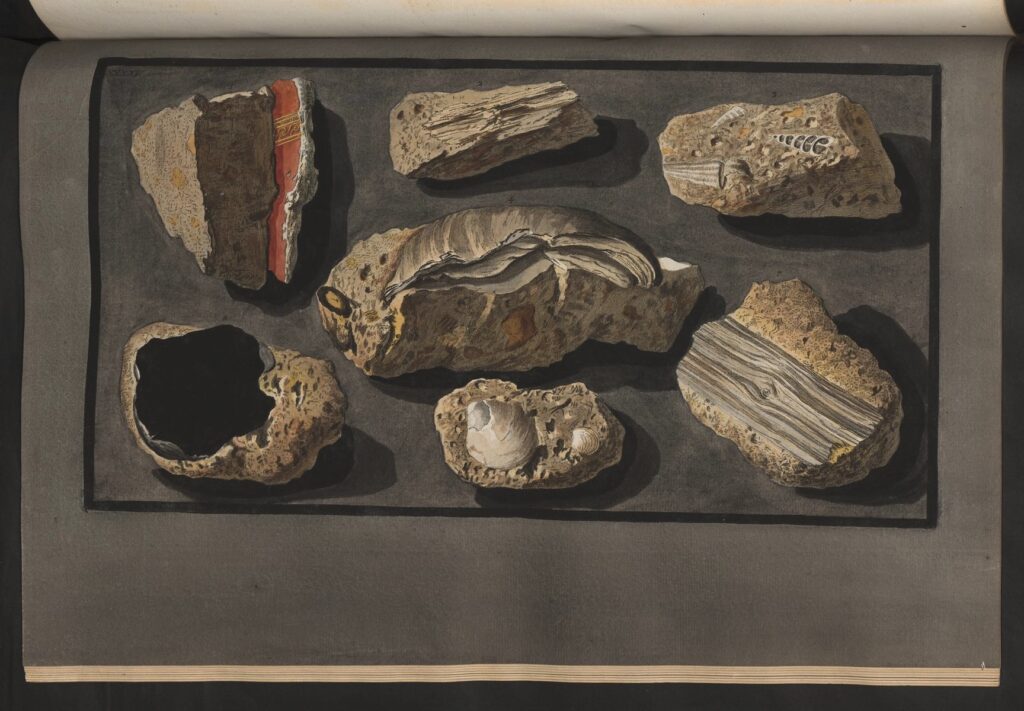

William HAMILTON, Campi Phlegraei. Observations on the Volcanoes of the Two Sicilies, as they have been communicated to the Royal Society of London by Sir William Hamilton K. B. F. R. S. His Britannic Majesty’s envoy extraordinary…, Napoli, Pietro FABRIS (editore nel senso di venditore esclusivo), Francesco MORELLI (stampatore) 1776. Tavola XXXXV. Acquaforte colorata a mano, cm. 39 x 21,5. Autore della gouache originale: Pietro FABRIS. Incisore e coloritore: Anonimo.

La tavola, come le altre della serie “litologica” di tredici tavole (tavole XXXXII-LIIII) che concludono l’apparato illustrativo dei Campi Phlegraei, va inquadrata nel ricco filone iconografico legato ai musei lapidari, di contenuto sia scientifico che antiquariale, affermatosi specialmente tra XVII e XVIII secolo.

Bibliografia. Sul dibattito scientifico settecentesco relativo al diverso meccanismo vulcanico di seppellimento di Ercolano e Pompei cf. Ciarallo 2006, pp. 17 e ss.. Sugli interessi mineralogici di Hamilton, cenni in Vickers 1997, in part. p. 264. Su Hamilton: Knight 1990 e Jenkins and Sloan 1996. Sulle vicende editoriali: Knight 2000, in part. pp. 34-35; Jenkins and Sloan 1996, in part. 165-7; Wood 2006.

TEORIE

Geologia e archeologia.

Teoria globale.

Il pezzo di tufo adeso ad un frammento di intonaco dipinto ritrovato ad Ercolano (fig. 1, in alto a sinistra nella tavola), città che le fonti antiche attestavano essere stata sepolta a seguito di una eruzione vulcanica, consente ad Hamilton di dimostrare che anche i simili tufi rinvenibili in altre aree della Campania (Baia, Capodimonte, Posillipo; figs. 2-7 nella tavola) avevano origine vulcanica. I materiali rinvenuti nello scavo di Ercolano, la cui origine vulcanica è attestata dalle fonti antiche (Plinio etc.), diventano il termine di confronto e di partenza per una ricostruzione relativamente “globale” della analoga genesi vulcanica di una intera regione, ben oltre il territorio vesuviano.

[Didascalia della tavola] 1. Piece of Tufa attached to a piece of the painted stucco of the inside of the ancient theatre of Herculaneum. The theatre of Herculaneum is filled with this kind of volcanick matter, and not with lava…which formed a tufa perfectly similar (as appears by this plate) to the tufas of Pausilipo and Baia. There can not be a more satisfactory proof of the volcanick origin of this kind of stone.

[p. 57] …The matter which covers the ancient Town of Herculaneum is not the produce of one eruption only… [p. 58] is not of that foul vitrified matter called lava, but of a sort of soft stone, composed of pumice, ashes and burnt matter. It is exactly of the same nature with what is called here the Naples stone. [p. 59] As much may be inferred from the exact resemblance of this matter, or tufa, which immediately covers Herculaneum, to all the tufas of which the high grounds of Naples and its neighbourhood are composed. I detached a piece of it sticking to and incorporated with the painted stucco of the inside of the theatre of Herculaneum, and shall send it for your inspection.

Il ruolo dell’acqua.

La presenza di tufo, invece dei depositi piroclastici non coesi di Pompei, spinge Hamilton ed altri naturalisti contemporanei ad ipotizzare un diverso meccanismo vulcanico di seppellimento delle due città. La presenza, nel tufo sopra l’antica Ercolano, di resti di legno carbonizzato ma non consumato, spinse Hamilton e altri ad attribuire un ruolo all’acqua, come elemento che impedì al fuoco di consumare i legni. Si delinea l’ipotesi della eruzione di un fango vulcanico che poi indurì in tufo. Hamilton basò la sua ipotesi anche su relazioni relative alla emissione di getti di materiali vulcanici misti ad acqua nel corso della emersione del Monte Nuovo vicino a Pozzuoli nel 1538 e nel corso della eruzione del Vesuvio del 1631 (Campi Phlegraei, pp. 70 e ss.).

[Didascalia tav. XXXX] …but when wood and shells are found in tufa (see P. XXXXV) (which probably was thrown out of its parent volcano in the state of a liquid mud) they have no appearence of having been affected by fire.

[p. 59. Sul tufo] …It is, I believe, a sort of lime prepared by nature. This, mixed with water, great or small pumice stones, fragments of lava and burnt matter, may naturally be supposed to harden into a stone of this kind; and, as water frequently attends eruptions of fire, as will be seen in the accounts I shall give of the formation of the new mountain near Pozzoli, I am convinced the first matter that issued from Vesuvius, and covered Herculaneum, was in the state of liquid mud.

Hamilton distingue tuttavia una primissima fase eruttiva, nella quale su Ercolano prevalse l’azione sola del fuoco: as the wood of the theatre [di Ercolano] is in general burnt, it is probable that the eruption of Vesuvius had first covered that unfortunate City with a shower of hot matter, and that afterwards its ruin was completed by a deluge of volcanick ashes mixed with water…[Didascalia della tav. XXXXV]

Hamilton è anche indotto ad ipotizzare una origine marina dell’acqua eruttata nelle prime fasi di eruzione: [p. 65, nota (a) a commento di un brano di Braccini relativo al rinvenimento di conchiglie sul Vesuvio nel corso della eruzione del 1631] this circumstance would induce one to believe that the water thrown out of Vesuvius, during that formidable eruption, came from the sea. Cf. anche Hamilton, 1776, tav. XXXXVII.

ROCCE E DEPOSITI

Tufi

L’origine vulcanica dei tufi nella regione intorno a Napoli non era chiara e scontata all’epoca. Hamilton ne dimostra la genesi vulcanica utilizzando come termine di confronto i tufi sovrastanti l’antica Ercolano, il cui seppellimento avvenne, come attestato da Plinio e altri autori classici, a seguito di una eruzione. Hamilton considera i tufi come fanghi vulcanici che in un secondo momento solidificarono.

Domenico Laurenza