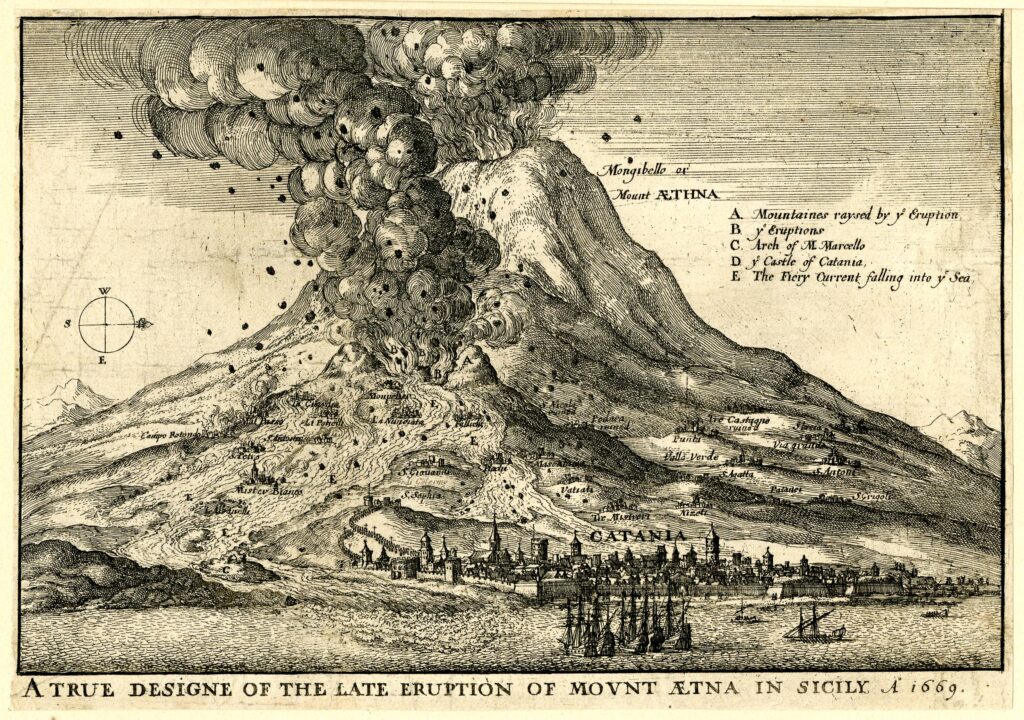

Heneage Finch, Earl of WINCHILSEA, A True and Exact Relation of the Late Prodigious Earthquake & Eruption of Mount Aetna, or, Monte-Gibello, London, Thomas NEWCOMB, 1669. Acquaforte. Incisore: Wenceslaus HOLLAR.

Heneage Finch, conte di Winchelsea, fu ambasciatore britannico a Costantinopoli dal 1660 al 1669. Durante il viaggio di ritorno in Inghilterra al termine della sua missione diplomatica, fece tappa a Catania, dove fu ospite del vescovo e poté assistere alla grande eruzione dell’Etna iniziata qualche settimana prima del suo sbarco. In seguito, arrivato a Napoli, scrisse al sovrano Carlo II una lettera (datata 27 aprile, 7 maggio 1669) che conteneva una descrizione degli eventi di cui era stato testimone oculare ed era accompagnata da un’illustrazione.

La lettera fu stampata a Londra in quello stesso anno, unita a due relazioni sulle prime fasi dell’eruzione che – almeno in parte – Winchilsea si era procurato in Sicilia grazie al vescovo di Catania. Nel volume compare anche una tavola opera di Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677) – prolifico incisore ceco che lavorò in Germania e poi a Londra – forse eseguita a partire dal disegno inviato in allegato alla lettera al re. Winchilsea scriveva di averlo fatto realizzare a Catania, non senza difficoltà, e prometteva un’ulteriore illustrazione che avrebbe fornito dettagli anche sull’avanzamento della lava in mare:

[p. 8] “As Your Majesty will see by the draught that I take the boldness to send herewith; it was the best I could get, but hath nothing of the Progress into the Sea; the confusion was so great in the City, which is almost surrounded with Mountains of Fire, that I could not get any to draw one, but I have taken care to have one sent after me for Your Majesty”.

Bibliografia. Anderson 2004; Godfrey 1994; Pennington 1992, p. 198, n. 1124. Sull’eruzione del 1669: Guidoboni et al. 2014; Abate e Branca 2015; Abate e Branca 2016; Branca 2019; Branca e Abate 2019; Branca, Del Carlo, Behncke, Bonfanti 2025.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

MAPPE

La tavola – accompagnata da indicazioni toponomastiche e da una legenda – rappresenta Catania, i paesi della zona pedemontana dell’Etna e tutto l’edificio vulcanico, con la bocca dei Monti Rossi e il cratere centrale in eruzione. L’Etna appare aguzzo e scosceso ed è quindi raffigurato in maniera meno realistica rispetto alle incisioni, relative alla medesima eruzione, contenute nelle opere di Borelli e di Tedeschi Paternò. Un’ulteriore differenza consiste nel punto di vista da cui è ritratta la scena, posto molto più in basso rispetto alle vedute a volo d’uccello delle tavole citate.

L’immagine permette di osservare l’estensione della colata lavica e l’ampiezza delle distruzioni da essa prodotte:

[pp. 5-6] “This River of Fire […] melts the Stones and Cinders by fits in those places where it toucheth them, over and over again; where it meets with Rocks or Houses of the same matter (as many are) they melt and go away with this Fire; where they find other compositions they turn them to lime or ashes”.

COLATE LAVICHE

La grande colata lavica è raffigurata come un impetuoso torrente, che avvolge i colli più elevati e, con le sue diramazioni nelle campagne di Catania, colpisce villaggi e resti archeologici (C – Arch of M. Marcello), arrivando alle porte della città. Winchilsea fu particolarmente colpito dalla lunghezza e dalla larghezza della colata, che paragonava a un’alluvione di materia infuocata:

[p. 4] “That extraordinary Fire, which comes from the Mount Gibel 15 miles distant from that City; which for its horridness in the aspect, for the vast quantity thereof, (for it is 15 miles in length, and 7 in breadth) for its monstrous devastation, and quick progress, may be termed an Inundation of Fire, a Floud of Fire, Cinders and burning Stones”.

Salito su una torre, l’autore riuscì a osservare fino a una grande distanza la colata e le grosse pietre da essa trascinate come da un fiume di fuoco:

[p. 7] “I could discern the River of Fire to descend the Mountain of a terrible fiery or red colour, and stones of a paler Red, to swim thereon, and to be, some as big as an ordinary Table. We could see this fire to move in several other places, and all the Country covered with Fire, ascending with great Flames”.

Secondo Winchilsea, la lava era composta da zolfo, mercurio, e altri metalli. Diversa era l’opinione espressa da Borelli 1670, che considerava la lava come roccia fusa:

[p. 6] “The composition of this Fire, Stones and Cinders, are Sulphur, Nitre, Quick-silver, Sal-Amoniac, Lead, Iron, Brass, and all other Mettals”.

La colata ha un moto irregolare, e avanzando più o meno velocemente modifica l’orografia della zona:

[p. 6] “It moves not regularly, nor constantly down hill; in some places it hath made the Valleys Hills, and the Hills that are not high are now Valleys”.

COLONNA ERUTTIVA

Nubi vulcaniche

Pietre infuocate

Nella tavola, la bocca laterale e il cratere centrale emettono alte colonne di fumo, ma anche fiamme, la cui altezza è paragonata a quella di un alto campanile. Dai Monti Rossi, inoltre, vengono scagliate in aria anche grosse pietre che sembrano ricadere su una vasta area circostante:

[p. 7] “I could plainly see at 10 miles distance, as we judged, the Fire to begin to run from the Mountain in a direct line, the flame to ascend as high and as big as one of the highest and greatest Steeples in Your Majesties Kingdoms, and to throw up great Stones into the Air”.

MUTAMENTI OROGRAFICI

Emersione di nuovi coni o nuove bocche eruttive

Benché anche il cratere centrale appaia in piena attività, l’illustrazione riserva un posto centrale alla bocca laterale dei Monti Rossi (A – Mountaines raysed by ye Eruption), da dove sono emessi lava, fiamme e fumo. In un passaggio della sua lettera, Winchilsea sembra fare riferimento proprio ai due nuovi coni:

[p. 8] “In 40 dayes time it hath destroyed the habitations of 27 thousand persons, made two Hills of one, 1000 paces high, a piece, and one is four miles in compass”.

Avanzamento della costa

Una parte considerevole della lettera è dedicata allo sbocco in mare della corrente di lava e all’avanzamento della costa. Tuttavia – come riconosciuto dallo stesso autore – questo fenomeno riceve scarsa attenzione nell’incisione, dove si osserva solo un’increspatura o un ribollire del mare, o forse la produzione di vapori dovuti all’impatto tra la lava e l’acqua (E – The Fiery Current falling into ye Sea):

[pp. 4-5] “burning with that Rage as to advance into the Sea 600 yards, and that to a mile in breadth, which I saw; and that which did augment my admiration was, to see in the Sea this matter like ragged rocks, burning in four fathom water, two fathom higher then the Sea it self, some parts liquid and moving, and throwing off, not without great violence, the stones about it, which like a crust of a vast bigness, and red hot, fell into the Sea every moment, in some place or other, causing a great and horrible noise, smoak and hissing in the Sea; and thus more and more coming after it, making a firm foundation in the Sea it self”.

TEORIE E INTERPRETAZIONI

Modello tecnologico

A proposito della lava che si estende:

[p. 7] “smoaking like to a violent furnace of Iron melted”.

Fabio Forgione